FLASHBACK FRIDAY: BRAD LACKEY’S WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP QUEST

Brad racing his way to be the first American to win a Grand Prix title.

Brad racing his way to be the first American to win a Grand Prix title.

The infancy of motocross in America was a time when European stars, such as Roger DeCoster, Torsten Hallman and Lars Larsson, shed light on what it took to be successful in the then-unfamiliar sport. America’s neophyte racers lacked the skill and experience required to topple the Euros, but they made up for those shortcomings with unwavering pride and fierce determination.

Berkeley, California, native Brad Lackey led the charge. Opinionated and steadfast in his resolve, Lackey was determined to raise the stars and stripes over the fleet of European ironmen that had dominated the scene on every continent. Brad quickly became the top American in the popular Trans-AMA series but was outgunned by a who’s who of Europe’s greatest motocross generation—Roger DeCoster, Ake Jonsson, Heikki Mikkola, Arne Kring, Adolf Weil, Joel Robert and others. Brad said, “The Europeans taught us that we needed to take our training much more seriously, and I took it to heart. From the beginning, I knew I wanted to go to Europe and compete against the top riders in the world.”

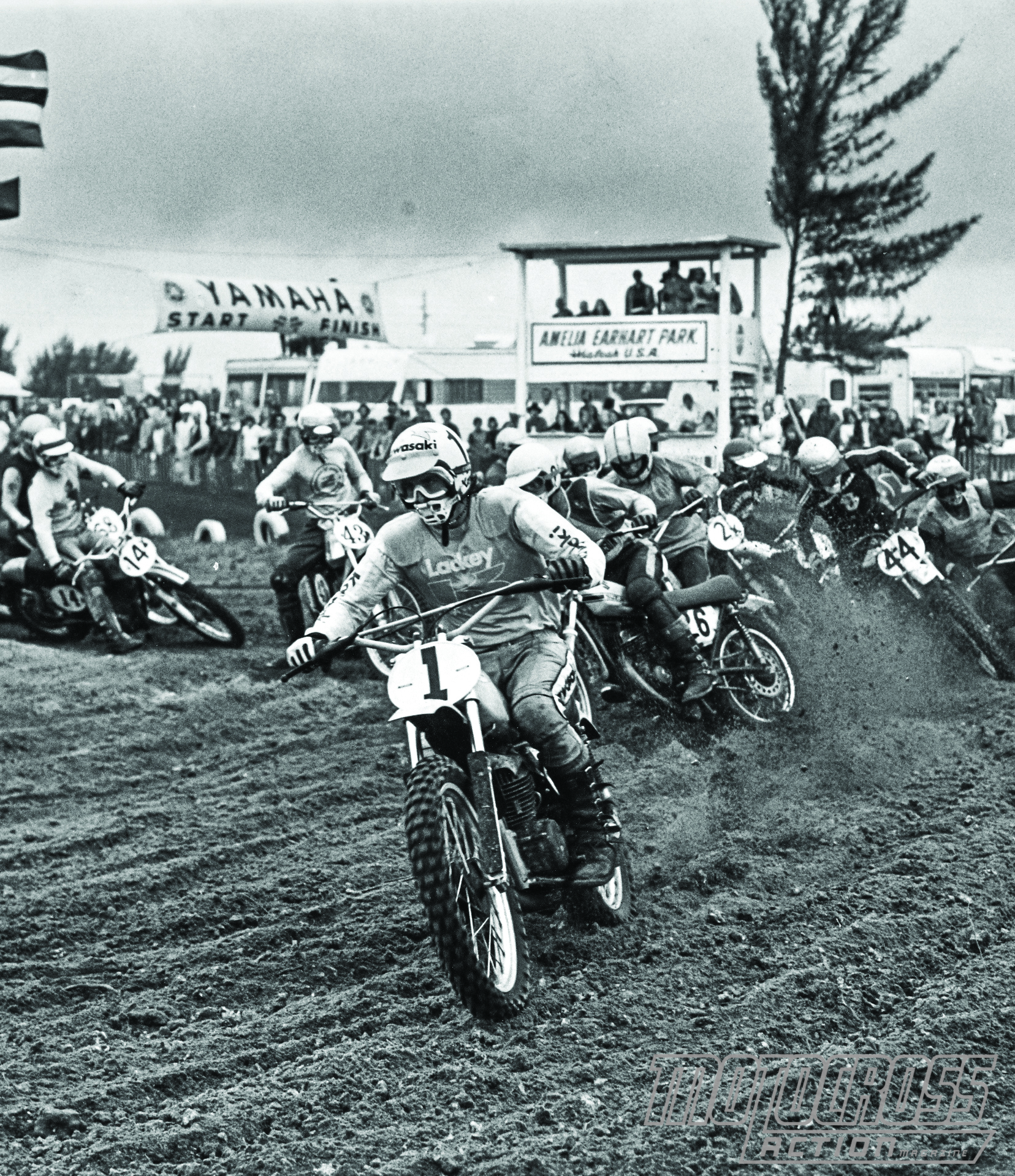

Brad won the 1972 AMA 500 National Championship and got to run the number one plate at Amelia Earhart Park in 1973.

Brad won the 1972 AMA 500 National Championship and got to run the number one plate at Amelia Earhart Park in 1973.

Lackey soon got his wish. In 1971, while racing for CZ , Brad was sent to Czechoslovakia for a training camp. While there, he contested several 250 Grand Prix races and got a taste of European culture; however, “Bad” Brad hadn’t yet committed himself to the GP series. Instead, he returned home and promptly won the 1972 AMA 500cc National Championship for Kawasaki. Lackey was unstoppable, winning five of the eight rounds.

“IN 1981 LACKEY JUMPED TO SUZUKI. SUZUKI HADN’T WON A WORLD TITLE SINCE ROGER DECOSTER BROUGHT THE YELLOW BIKES GOLD IN 1975. LACKEY AND HIS CREW STARTED FROM SCRATCH AND HAND-BUILT THEIR OWN VERSION OF THE BEST POSSIBLE SUZOOK–OFTEN FORSAKING WORKS PARTS FOR AMERICAN PARTS.”

Naturally, Kawasaki wanted its star to defend the AMA 500cc crown in 1973, but Brad Lackey had other ideas. Fighting common sense and going against Kawasaki’s wishes, Lackey packed his bags and headed to Europe. With minimal support from Kawasaki, Brad struggled through the 500cc GP season that year. It was understandable that Kawasaki wanted nothing to do with Lackey in 1974. Fortunately, Husqvarna saw promise in the young American.

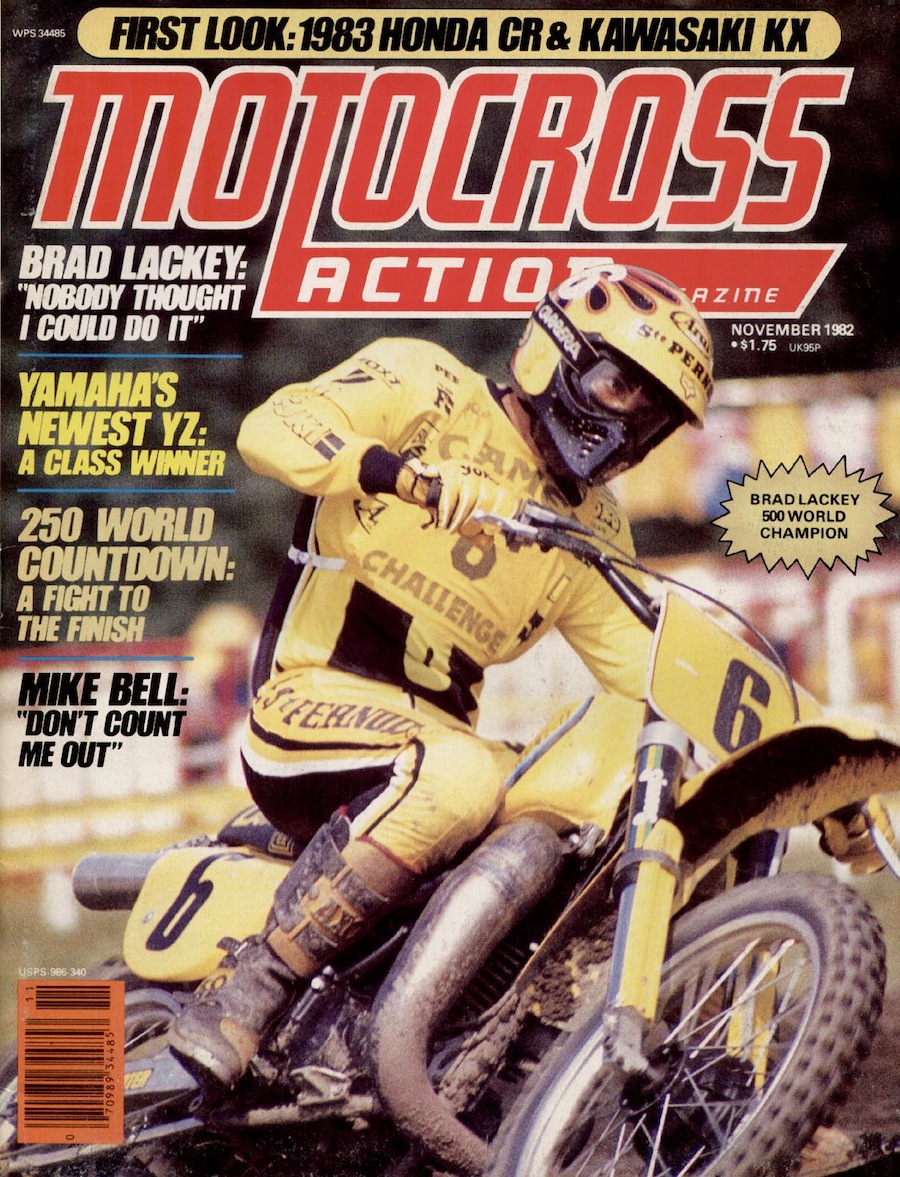

Brad on the cover of the November issue of 1982 after he was the first American in history to win a Grand Prix title.

Brad on the cover of the November issue of 1982 after he was the first American in history to win a Grand Prix title.

After three years on the Swedish brand, Lackey moved to Honda. He won his first Grand Prix at the 1977 British round and finished second overall in the 1977 World Championship standings to Heikki Mikkola. Somehow Brad ended up at Kawasaki again and completed a two-year stint with the Japanese brand in 1979 and 1980—although he fell short in his quest for the title. In 1981 Lackey jumped to Suzuki. Suzuki hadn’t won a world title since Roger DeCoster brought the yellow bikes gold in 1975. Lackey and his crew started from scratch and hand-built their own version of the best possible Suzook—often forsaking works parts for American parts. Suzuki wasn’t happy about it, but Brad’s goal was to win the 1982 FIM 500 World Championship—no matter what it took.

It didn’t come easy. Belgian sensation Andre Vromans cut into Lackey’s lead as the series wound down, and Vromans only trailed by four points heading into the final round in Luxembourg. In the first moto the Belgian jumped out to a 27-second lead over Lackey, but the American paced himself. With five laps to go, Brad poured on the coals and passed his rival with half a lap to spare. Vromans’ spirit was destroyed. The second moto was anticlimactic, as Andre was buried on the start, and Lackey rode cautiously to win the 1982 500cc GP title. In doing so, Brad Lackey became the first American to win a Grand Prix title. Another American, Danny LaPorte, followed suit a few weeks later by capturing the ’82 250cc title. Suzuki was glad to win the crown but unhappy with how Brad Lackey achieved it—and dropped him in 1983.

Comments are closed.